- About

-

Services

-

Offerings

- Offerings

- ADME and Bioanalytical Sciences

- Analytical Chemistry

- Assay Development

- Biochemical Assays

- Biophysical Assays

- Cell Based Assays

- Computational Chemistry

- Fragment and Compound Screening

- Integrated Drug Discovery Services

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Project Management and Consultancy Services

- Protein Expression and Purification Services

- Structural Biology

- Synthetic Chemistry

- Virtual screening

-

Research Phases

- Research Phases

- Hit Identification

- Hit to Lead

- Lead Optimisation

- Therapeutic Areas

- Target Classes

-

Approaches & Techniques

- Approaches & Techniques

- CDH (Target Gene Fragmentation)

- Cryogenic Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM)

- Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) and nanoDSF Services

- Direct-to-Biology (D2B)

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

- eProtein Discovery

- Flow Cytometry

- Fragment Based Drug Discovery (FBDD)

- FragmentBuilder

- Grating-Coupled Interferometry

- High Throughput Screening

- Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC)

- LeadBuilder

- PoLiPa (Membrane Protein Solubilisation)

- Spectral Shift and MST Services

- Structure Based Drug Design (SBDD)

- Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)

- X-ray Crystallography

-

Offerings

- Library

- News & Events

- Careers

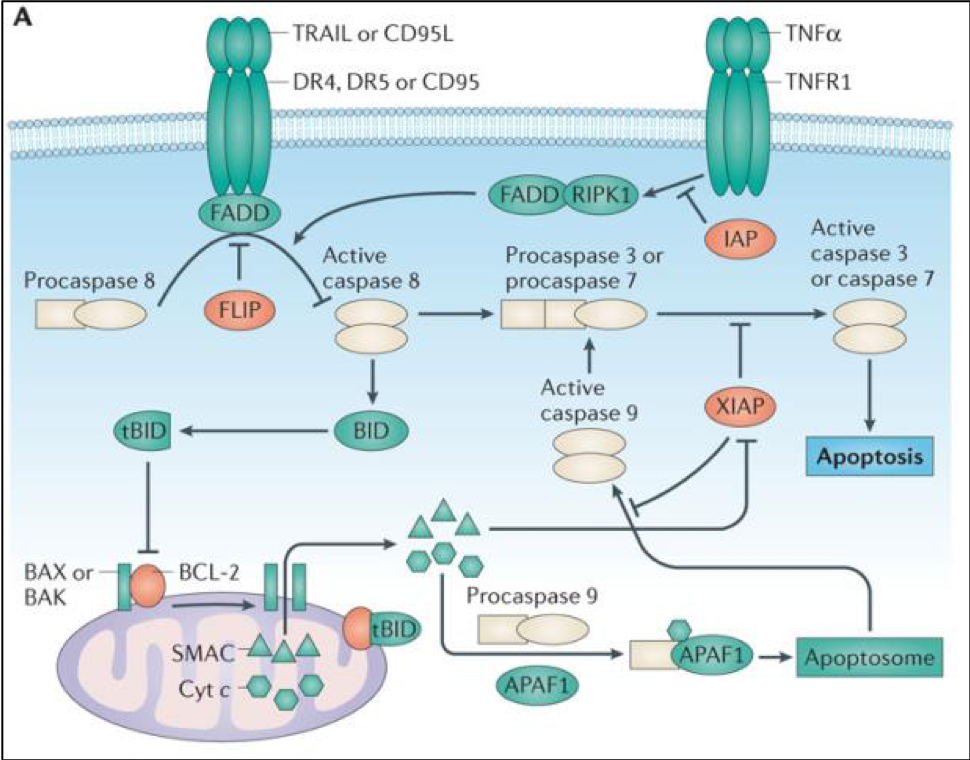

FLIPP-FADD: PPI inhibitors for the treatment of solid tumours

FLIP is a non-redundant inhibitor of caspase 8 activation which mediates apoptosis. Over-expression of FLIP is a tumour cell survival mechanism, and hence FLIP is of interest for the treatment of a number of cancers including lung cancer.

Challenge

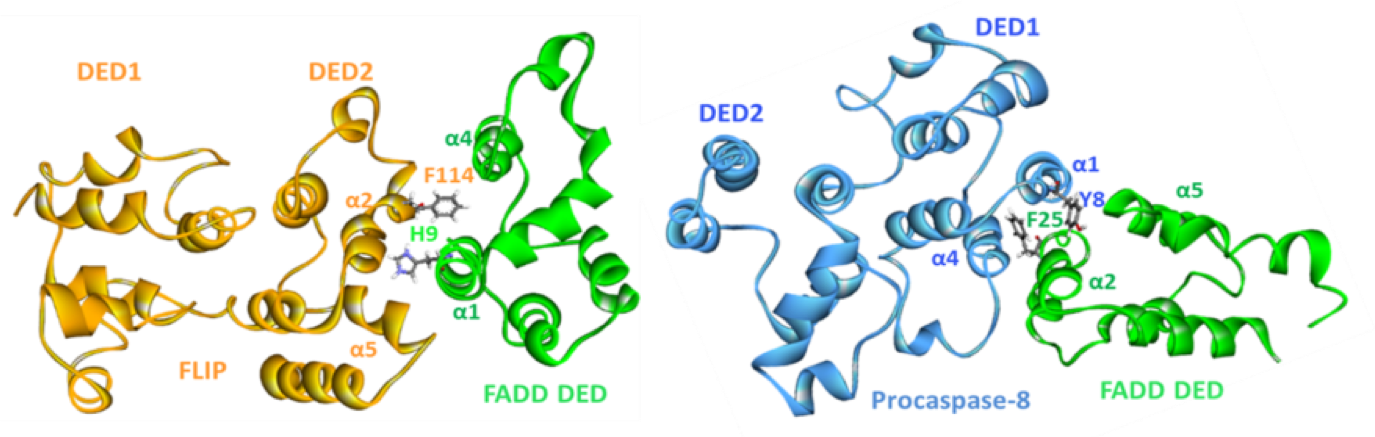

When this project was started, the FLIP-FADD protein-protein interaction (PPI) was widely thought to be 'undruggable', partly because the structural details of this binding were unknown, but also due to a further problem: it was believed that the procaspase 8 and FLIP binding modes were analogous, and so it would be impossible to find a compound that would inhibit FLIP binding, but be permissive to the procaspase 8–FADD interaction that is required for apoptosis to proceed. When Prof. Dan Longley’s group at Queen’s University Belfast used extensive protein mutagenesis data and molecular modelling to understand these two binding events, they realised that there were significant differences in their binding modes (Figure 2), and a therapeutic opportunity was recognised.1 The aim was therefore to use rational design based on this understanding in order to find selective inhibitors of the FLIP-FADD PPI.

Solution

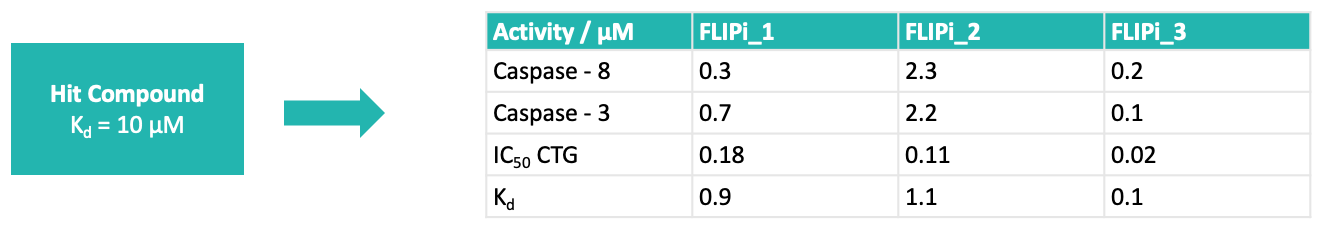

Longley’s group identified a druggable cleft on the surface of the DED2 domain of FLIP by molecular dynamics studies on the protein, and their modelling suggested that the binding of an α-helix of FADD into this cleft was a key element of the PPI. This hypothesis was supported by mutagenesis studies and offered an opportunity to use a rational design approach to find selective binders to FLIP that would inhibit the PPI with FADD, but would not bind to procaspase 8. Domainex’s CADD scientists used the proposed binding cleft to design pharmacophoric search protocols with their proprietary virtual screening platform, LeadBuilder. This was used to select a compound screening set of around 1000 compounds, covering multiple chemotypes, which were evaluated in a medium-throughput screen. A handful of structurally unrelated compounds were identified which showed binding to FLIP at 10uM.Three of the hits were selected for further investigation, and optimisation of their potency and pharmacokinetic properties led to a viable lead and back-up series.

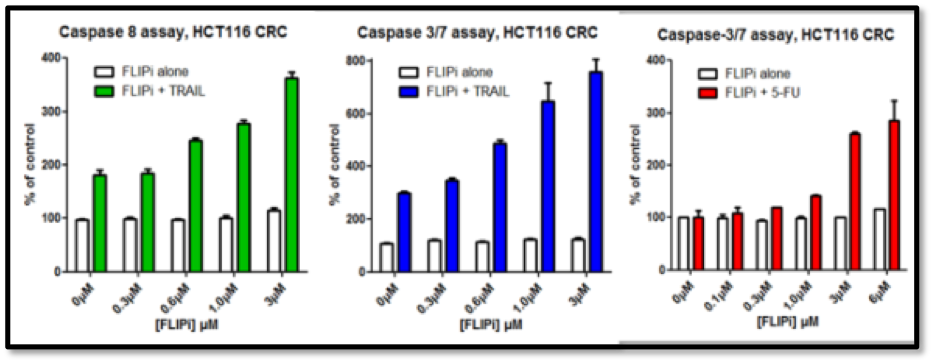

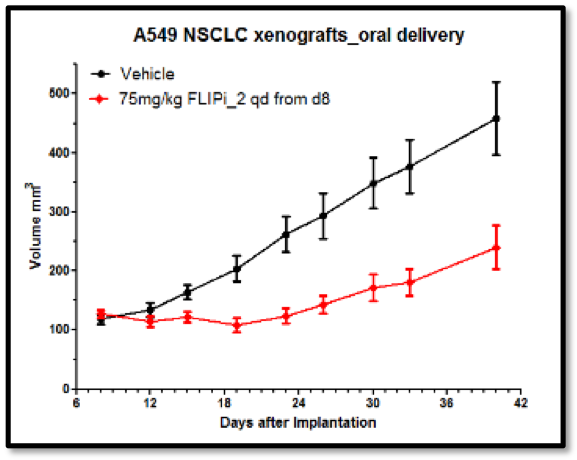

The Longley group showed that the compounds had excellent cell activity (Figure 5), good in vivo PK (Figure 4) and in vivo activity in murine xenograft studies (e.g. Figure 6). Their selectivity with respect to procaspase 8 binding was confirmed in mechanistic cellular assays, and broader specificity was established in a Eurofins Safety 44 panel.

| FLIPi_2 | |

|---|---|

| CLint (Hep, mouse)* | 55 |

| PPB (% bound, mouse) | 69 |

| Caco-2, Papp A-B (efflux)§ | 7.6 (1.4) |

| MW | <350 |

| Log D (measured) | 1.0 |

| Log P (calculated) | 2.6 |

| *μL/min/106cells; § x 10-6 cm-1 | |

This programme is currently at the pre-clinical candidate nomination stage and several companies are carrying out due diligence with regards to taking it on for further development.

Conclusions

Starting with an innovative hypothesis developed by our academic collaborators in Belfast, virtual screening using LeadBuilder, and hit optimisation by the Domainex medicinal chemistry team led to the world’s first inhibitors of the FLIP-FADD interaction. These compounds have been designed and shown to have high specificity for FLIP, and to have a good PK profile. Testing in murine xenograft experiments has provided proof of concept for this anti-tumour mechanism, and further development of the chemistry has provided a range of pre-clinical candidates.

This programme was funded in part by the Wellcome Trust Seeding Drug Discovery scheme.

Domainex Expertise

• Integrated Drug Discovery • Virtual Screening via LeadBuilder • Hit Identification • Computational Chemistry • Hit-to-lead • Lead Optimisation

• Medicinal and Synthetic Chemistry • DMPK and ADME • Safety Pharmacology • Protein-protein Interaction Drug Discovery • Oncology

Reference

- Differential affinity of FLIP and procaspase 8 for FADD’s DED binding surfaces regulates DISC Assembly. J. Majkut, M. Sgobba, C. Holohan, N. Crawford, A.E. Logan, E. Kerr, C.A. Higgins, K.L. Redmond, J.S. Riley1, I. Stasik, D.A. Fennell, S. Van Schaeybroeck, S. Haider, P.G. Johnston, D. Haigh and D.B. Longley. Nat Commun., 2014, 5, 3350.

Press releases

Queen's University Belfast and Domainex Win Late-Stage Award to Progress Novel Lung Cancer Drug Candidate into the Clinic

26th April 2016

Queen’s University Belfast and Domainex in Cutting-Edge Collaboration to Advance Novel Lung Cancer Drug Research

17th April 2017

Start your next project with Domainex

Contact one of our experts today